Digital Community Entrepreneurs: Testing Their Effectiveness in Driving Uptake of Digital Financial Services in Rural Areas of Uganda

Contact

Value Chain and DFS Consultant

UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF)

Tags

The challenge of driving uptake of mobile money and related digital financial services (DFS) among last-mile rural communities is real. On the demand side, a significant obstacle is the need for farmers to acquire a mobile phone, a SIM card, the means of charging the phone, the knowledge to use the service, and of course an understanding of why they should want to pay for all of these things instead of accepting the status quo.

The challenge of driving uptake of mobile money and related digital financial services (DFS) among last-mile rural communities is real. On the demand side, a significant obstacle is the need for farmers to acquire a mobile phone, a SIM card, the means of charging the phone, the knowledge to use the service, and of course an understanding of why they should want to pay for all of these things instead of accepting the status quo.

On the supply side, a big question is the sustainability of efforts to provide access, build awareness and ensure affordability of DFS among low-income, low-literacy and last-mile customers.

Smallholder agriculture in Uganda not only contributes enormously to GDP at the national level but also to food and nutrition security at the household level. Moreover, it is the single largest employer of women and young people. Roadblocks to their increased productivity and empowerment include climate change; limited access to extension, market and weather information; limited access to financial services; and few market connections, all of which have not been fully and/or satisfactorily addressed.

Recognizing these challenges in rural areas and, at the same time, the potential market opportunities with last-mile customers, the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) has been working with partner organizations in five major agricultural value chains (i.e., coffee, tea, dairy, maize and seed oil) for the past three years to introduce DFS to rural Ugandans. UNCDF has encouraged innovative approaches to address the challenges and has learned some key lessons along the way:

- Getting rural Ugandans to use a mobile wallet regularly is challenging, as the value proposition for DFS is not always evident to them. Moreover, uptake varies significantly based upon the dynamics of the particular value chain (e.g., crop seasonality and established trade links).

- Engaging formal or informal influencers (e.g., ‘lead farmers’) in a value chain has a positive impact on end-user engagement and adoption. If solutions address the needs of community leaders, these leaders become active promoters to onboard farmers as well as the broader community.

- Agricultural communities extend across multiple value chains as most farmers produce more than one crop. Mapping their behaviour can clarify how to position DFS so that the farmers find the services relevant and perceive them to have a higher value than cash.

These lessons inspired UNCDF to collaborate with the agro-fintech MobiPay AgroSys Limited to roll out a new last-mile distribution model: Digital Community Entrepreneurs (DCE). The DCE model uses experienced rural youth as agents to train and support smallholder farmers and producer organizations to overcome the barriers surrounding DFS awareness, adoption and usage. The model is crafted around the selection of opinion leaders within a community, people who are highly regarded and listened to by locals. Having these opinion leaders act as product champions for DFS helps accelerate top-of-mind awareness of the benefits of DFS, thus driving adoption and usage.

The critical learning question for the DCE model is the following: Is it possible for a private-sector company to sustainably deliver the required customer education for DFS as well as create and meet the demand for DFS, beyond the support of development partners?

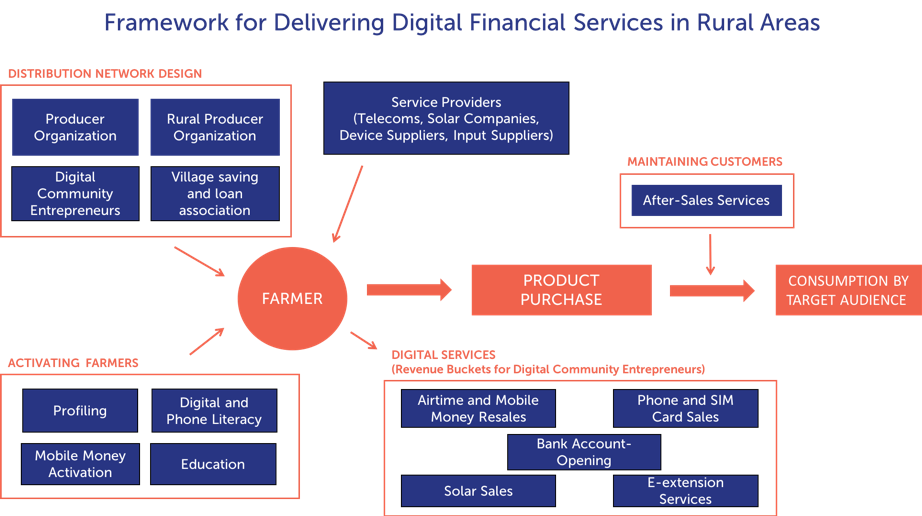

UNCDF and MobiPay launched a pilot of the DCE model in November 2018 in the Lango sub-region (seed oil value chain) and the Busoga sub-region (maize value chain). As illustrated in figure I, MobiPay (a) identifies DCEs within the pilot community and (b) trains and equips them to (i) profile farmers; (ii) educate farmers, specifically to improve their digital and mobile-phone literacy; and (iii) cell phones, SIM cards, solar home systems, airtime top-ups and mobile money services, on which they earn commission. Additionally, DCEs promote clean energy products and help farmers better understand and use e-extension information received via mobile phone. Eventually, the goal is for DCEs to help foster digital bulk payments to smallholder farmers. Most importantly, as a business-oriented model, the youth who serve as DCEs are empowered through the acquisition of entrepreneurial skills and gain financial stability through their sales/commissions. For its part, UNCDF facilitates agreements between MobiPay and manufacturers/distributors of products (e.g., mobile phones and solar home systems) as well as financial service providers.

Framework for delivering digital financial services to rural areas via Digital Community Entrepreneurs

MobiPay Managing Director Eric Nana Agyei described the organization’s role in the project thus: “We, as MobiPay, play a facilitative role of training [and] capacity and skills development of the Digital Community Entrepreneurs, aimed at making them good at cross-selling within the community. We believe that working with the local people, like the youth and … senior citizens open up doors and builds rapport between our company and the farmer community.”

Once farmers receive the initial orientation and access a mobile phone, they typically face hurdles to charging the phone and rebalancing the wallet. DCEs help address these issues by selling solar home systems to community members that allow them to charge the phone at home. The DCE model also emphasizes access for farmers to a broader range of affordable and relevant financial services, such as mobile money, digital payments, credit products and insurance products.

Early insights of the pilot reveal that (a) there are viable ‘revenue buckets’ for the DCEs, which can make their work sustainable and profitable, and (b) there are many important cross-cutting themes that will likely shape the adoption of DFS by farmers:

Early insights of the pilot reveal that (a) there are viable ‘revenue buckets’ for the DCEs, which can make their work sustainable and profitable, and (b) there are many important cross-cutting themes that will likely shape the adoption of DFS by farmers:

- DCE efforts spark a spiral of positive word-of-mouth in the community. Once a farmer has received education/training on DFS by a DCE and told by the DCE about the value proposition of DFS, it is easy to convert that farmer’s awareness into active usage and to use him/her as a referral for other farmers (i.e., the customer-refers-customer model). Isiiko, a maize farmer from Luuka, illustrates this point: “My neighbour told me that whenever he buys airtime through mobile money, he earns [a] 50 per cent bonus, and I also started using mobile money plus requested my leaders at the producer cooperative to pay my money through mobile money.”

- Agro-processors are a key entry point in these rural value chains. Most agricultural value chains that are organized have anchor/apex bodies that command the chain down to the last-mile beneficiary. These agro-processors are thus a valuable anchor partner and entry point to reach smallholder farmers.

- Door-to-door service provision is vital. Having a local team of subject-matter experts serve as product champions in rural areas brings financial services closer to farming communities. They have ample time to explain and showcase the value to end users and are trusted by the farmers.

Service providers seeking to implement DFS will need to provide personal, accessible touchpoints to build trusted relationships with farmers, an effort that indeed requires a significant amount of time. Over the next 12 months, UNCDF will be working on refining this model and applying lessons learned to scale the model up and reach more regions and value chains.