Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me: The lessons of history illustrate the critical role of local governments in pandemic responses. What have we learnt?

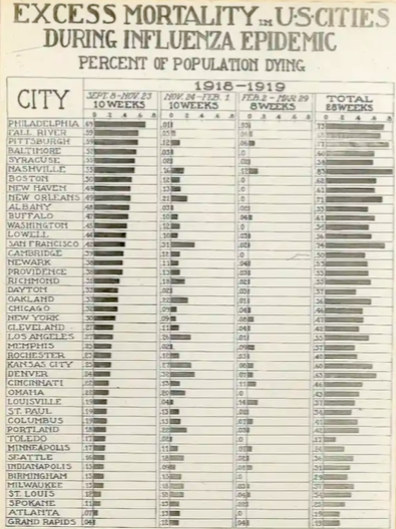

The chart above illustrates the difference in mortality rates between US cities during the 1918-1920 Pandemic.

Photograph: Public Domain. Relative number of deaths in US cities from the 1918 – 1919 flu pandemic.

Almost 100 years ago the “Spanish Flu” ravaged many parts of the world, rather like the Coronavirus is doing now. The Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 flu pandemic, was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic.

Lasting almost 36 months from January 1918 to December 1920, it infected 500 million people – about a third of the world's population at the time. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. The Spanish Flu was more deadly than the 1914 – 1918 War – though it faded into memory much faster.

It is interesting how quickly history is remade. The historical narratives we prefer are those of the changing nations and ideologies that arose from the 1914 – 1918 war. Yet, our descendants may view history differently – nations and ideologies may become insignificant alongside the more fundamental question of our human ecosystem. Future historians may study the gradual deterioration of the environmental pre-conditions for human life on earth. Why? They may ask. How could we be intelligent enough to develop artificial intelligence yet dumb enough to ignore the evidence that the ecosystem which sustains us is no longer sustainable? Will the first generation to understand that the planet does not need us, but we need it, be able to make the necessary changes quickly enough to avoid extinction? On current evidence, we have not yet reached this appreciation of the risk to our existence.

Our descendants may also focus on whether we learnt the lessons from previous pandemics like the Spanish Flu in addressing the Coronavirus. One of those lessons is the critical role of local governments as first responders and as facilitators of the lifestyles required to survive – ensuring that these are available for all. Data from the United States illustrates a clear correlation between the local government response and the different death rates in different cities of similar size and density.

Nancy Bristow, in American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (Oxford University Press, 2017) provides an account of the different responses by different parts of government and the different reactions from citizens and communities. In the light of what is happening now, the feeling of déjà vu is unavoidable with different individuals performing the same roles that are being played out today – those that want to open more quickly and those that are decisive in enforcing the lockdown. Yet, even our oldest stories such as the Ramayana, which has been retold and embellished for millennia, always has the same ending with each character representing specific aspects of human personality. Perhaps this is inevitable. Is it?

Nancy Bristow writes in the Guardian on April 29th 2020 that;

“What’s most useful to us today is the comparative experience of Philadelphia and Seattle. Philadelphia, despite having some warning that the pandemic was coming, did little to prepare…. Philadelphia continued to conduct business as usual. On 28 September 1918 it hosted a massive kickoff parade for the Fourth Liberty Loan, the bond drive used to support the American war effort. Three days later the city reported 635 new influenza cases, and the situation soon worsened. Though the city now moved to protect itself, Philadelphia was overwhelmed by the epidemic. Available healthcare resources, already compromised by the war effort, were quickly stretched past their limits. Morgues overflowing with the dead, a desperate shortage of coffins and a resort to mass graves resulted from the city’s failure to move early to prepare. Philadelphia suffered one of the nation’s highest death rates.

Seattle offers a very different story. On 20 September, the city’s commissioner of health, Dr JS McBride, acknowledged that “it was not unlikely” that influenza would reach the city and warned the citizenry that, if it did, isolating cases would be necessary. When soldiers at nearby Camp Lewis came down with the flu, the camp was quarantined. On 4 October, the story broke that large numbers of students at the naval training station at the University of Washington had contracted influenza. Within two days the city had, despite significant opposition, closed schools, prohibited church services and shuttered many public entertainments. Crowding was prohibited in those businesses still operating.

In the days to come, other measures followed. A local hotel was requisitioned for use as an emergency hospital. Spitting in public could mean a jail cell and public shaming, the wearing of masks was required in public, business hours were shortened, and further limitations were placed on those allowed to remain open. Though he had initially hoped the pandemic would pass in less than a week, the health commissioner maintained the restrictions, even as the number of cases began to decrease. Finally, on 11 November, both the city and state announced an end to closures and masking. Not uncommonly, the city soon faced a return of the disease. Again, the city acted, this time quarantining the sick. As a result of these actions, Seattle suffered one of the lower death rates on the West Coast, substantially lower than Philadelphia’s.” Nancy Bristow, Guardian, 29 April 2020

A critical lesson for today is that by capacitating local governments to prepare in advance it may be possible to mitigate the worst effects of the Coronavirus before the local health system is overwhelmed. UNCDF will continue to work with partners at both national and local level to design, implement and advocate for innovative financial mechanisms that make local government finance an effective tool to combat the Coronavirus and accelerate the recovery from it.

We are delighted that the importance of local government finance is acknowledged in the United Nations Secretary General’s April 2020 UN Framework for the Immediate Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19. The Secretary General’s report references the fourth edition of the UNCDF guidance note on local government finance and COVID-19 which includes an expanded section on Operational Expenditure Block Grants – one of the tools that can be deployed right now to ensure that there are more towns and cities around the world with responses like Seattle in 1918 and less with the experience of Philadelphia.

Blog entry written by David Jackson, david.jackson@uncdf.org

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_flu