From the Field to Policy Formulation – How Research is Informing Consumer Protection in Sierra Leone

Tags

In Sierra Leone, Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) has partnered with the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) and the Bank of Sierra Leone (BSL) to develop new policy diagnostics which uses applied research to measure experiences of consumers and the conduct of financial service providers.

This approach differs from traditional policy strategies which often focus on legal and regulatory reviews and stakeholder interviews as the primary sources of insights.

This research focused on consumer protection uses a diverse set of applied methods to analyze the current context and issues. These methods include:

- Consumer survey - Using a brief phone survey, we were able to contact more than 1,000 users of banks, microfinance, and mobile money products in a short time frame across the country.

- Administrative data analysis - Providers submitted deposit records and mobile money transactions, allowing for granular analysis of consumer usage patterns and costs of products.

- Product documents and policies - Providers submitted marketing and contract documents to measure current practices in transparency, and complaints handling policies to identify good practices for future complaints handling rules.

- Mystery shopping for complaint handling - Using consumers from the survey who had unresolved issues, we observed the ability of providers to resolve consumer complaints.

Each of these methods provided a different viewpoint on key consumer protection issues, and together helped to identify several policy priorities:

1. Fee transparency in banking is needed.

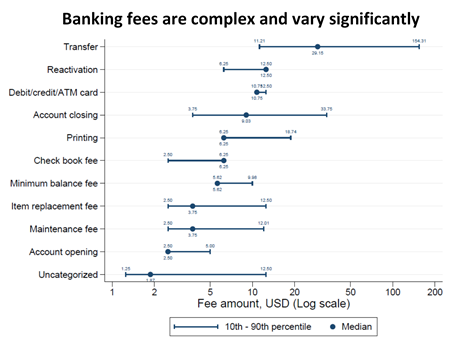

In the consumer survey, 59 percent of mobile money account holders said they understood the fee structure well or very well, compared to only 35 percent of bank account holders. Analysis of administrative data supported this transparency concern, as we found many more fee types on a typical deposit account than a mobile money account, which makes it harder to monitor costs on bank accounts versus mobile wallets. Figure 1 shows deposit account fees can vary for different customers. The transaction data also showed a noticeable difference in fees as a portion of the total balance for deposit account holders 24 years old or younger versus all other age demographics, suggesting that new users may be less aware of fees assessed on their accounts than other users. These findings point to the need for better standards on fee structures and fee transparency in banking, and perhaps financial capability training on fee structures and account usage to younger depositors.

2. Consumers face several risks from fraud and lost value.

37 percent of survey respondents reported sharing their PIN, 41 percent of consumers were targets of phishing phone or SMS scams, and 10 percent of users of mobile money agents claimed they charge them extra fees to transact “every time.” Each of these represents risks to consumers of fraud and lost value in their accounts, which can hinder trust and usage in the long-term. Fraud is an issue that affects both providers and consumers and may be an area where providers and regulators could collaborate to monitor and take action against third-party and agent fraud on an ongoing basis.

3. The best examples for policy sometimes come from providers’ current practices.

The complaints handling policies and data collection templates of providers in Sierra Leone included robust standards on access, resolution time, and complaints tracking. Where good policies are already in place, regulators can consider codifying best practices from the industry in new industry-wide standards. However, these practices should still be monitored for compliance, as the mystery shopping of complaints resolution found that complainants faced waiting times of up to an hour or more, and only 1 of 18 complaints were given a tracking number for follow-up, signaling areas for improvement in staff compliance with providers’ complaints handling policies.

Much of the data described above is data that regulators can access relatively easily through information requests or can roll out quickly in the case of phone surveys and follow-up mystery shopping with survey respondents. While we usually think of information requests as something done after the rules are written to monitor compliance, we hope that our experience in Sierra Leone encourages more policymakers to consider research methods as an input to the policy development process as well.

With this data, UNCDF is helping Bank of Sierra Leone to draft and publish financial services consumer protection guidelines with an objective of improving consumer confidence in the formal financial system.