Local Government Rising: Somalia’s fiscal decentralisation success story

Mkhululi Ncube – Mkhululi.ncube@uncdf.org

Programme Manager, Mogadishu Somalia

Amadou Sy - Amadou.sy@uncdf.org

Local Transformative Finance Communication

Tags

In Somalia, almost three million people have been displaced, as result of conflicts and natural disasters. Although the north of the country is largely peaceful and calm, the south remains volatile, with pockets of instability where insurgent forces compete with the government for economic resources and revenues.

Conflicts among clans over resources have complicated the Somali security situation. In addition to these conflicts, in recent years, the country has experienced devastating natural disasters, including floods, the worse drought in 40 years, and locust swarms. Rural and pastoralist farmers have flocked to cities, putting additional pressure on the limited urban infrastructure, and Somalia is on the brink of a humanitarian tragedy as a result of food and water insecurity (made worse by the Ukraine-Russia conflict) and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet, despite this gloomy picture, success stories are emerging in Somalia, especially in the broader fiscal decentralisation thematic area. UNCDF would like to share some highlights of these successes from the Local Development Fund (LDF) − a discretionary, multi-sectoral, performance-based grant for local governments.

The LDF in Somalia

Close to fifteen years ago, Somalia, with the support of the United Nations Joint Programme on Local Governance (JPLG) and driven by the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), embarked on the fiscal decentralisation journey, with the LDF as the principal vehicle for fiscal decentralisation. The LDF was introduced into Somalia’s subnational ecosystem in 2011. The LDF is UNCDF’s flagship project in Somalia and designed to promote equitable and effective service delivery and infrastructure development, and so enhance the legitimacy of fledgling local governments. Its five objectives are:

• To provide discretionary capital and sectoral grants at the local level

• To incentivise fiscal decentralisation reforms

• To develop planning, budgeting, budget utilisation, monitoring and evaluation, and reporting capacity at the local government level

• To provide resources for local development and service delivery

• To develop and enhance own revenue mobilisation for municipalities

• To promote good governance and decentralised service delivery

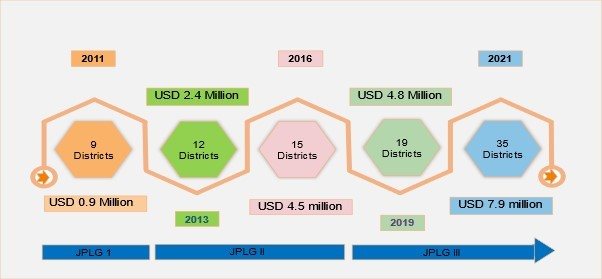

Figure 1: LDF investments since 2011

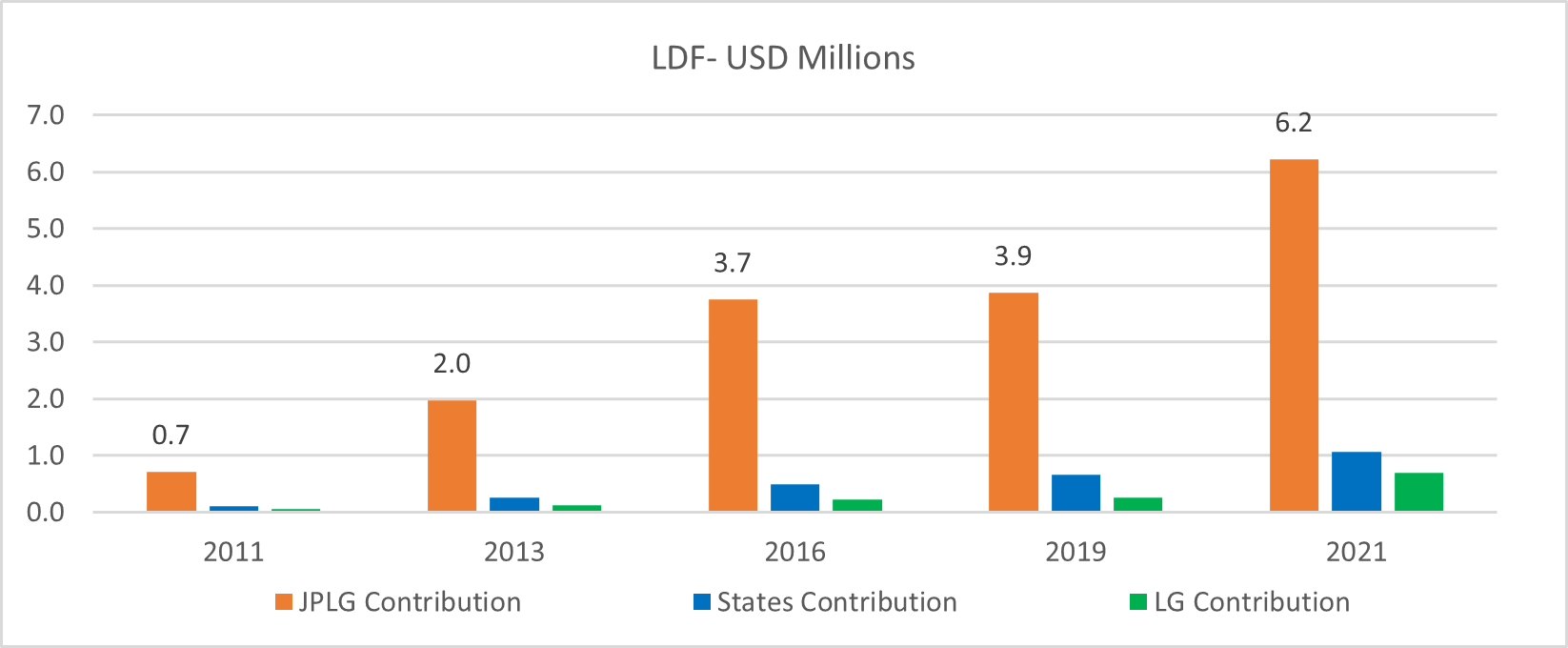

Figure 2: Breakdown of LDF funding sources (2011−2021)

The LDF uses a transparent allocation formula and incorporates a performance component that promotes a high degree of compliance with public finance management best practices and procedures. The fund is capitalised by development partners through the JPLG and the different states and districts, (albeit in varying amounts), stimulating high levels of community ownership.

The LDF Success Stories

LDF’s growing footprint

Over the past decade, the fiscal decentralisation footprints of local governance reforms have grown in leaps and bounds, from covering eight districts in 2011 to 35 districts in 2022. In 2011, almost US$1-million was transferred to local authorities through the LDF; in 2021 (ten years later), US$8-million was transferred to municipalities by UNCDF through the LDF. Between 2011 and 2021, JPLG disbursed a total of US$16.5-million through the LDF grants (Figures 1 and 2). Ten years ago, intergovernmental transfers were rare, unpredictable and small. Currently, different levels of government are able to work together in planning, contracting, overseeing and paying for goods and services.

Since adopting fiscal decentralisation in 2013, Somaliland and Puntland have endeavoured to perfect their intergovernmental fiscal relations system. Even those local authorities not covered by JPLG have adopted JPLG systems and processes for transferring or mobilising resources to municipalities. They use the same bidding, procurement, and contracting procedures developed by JPLG. The LDF has, to a large degree, achieved its objective of building legitimacy, capacity and systems for effective decentralised services in many parts of Somalia.

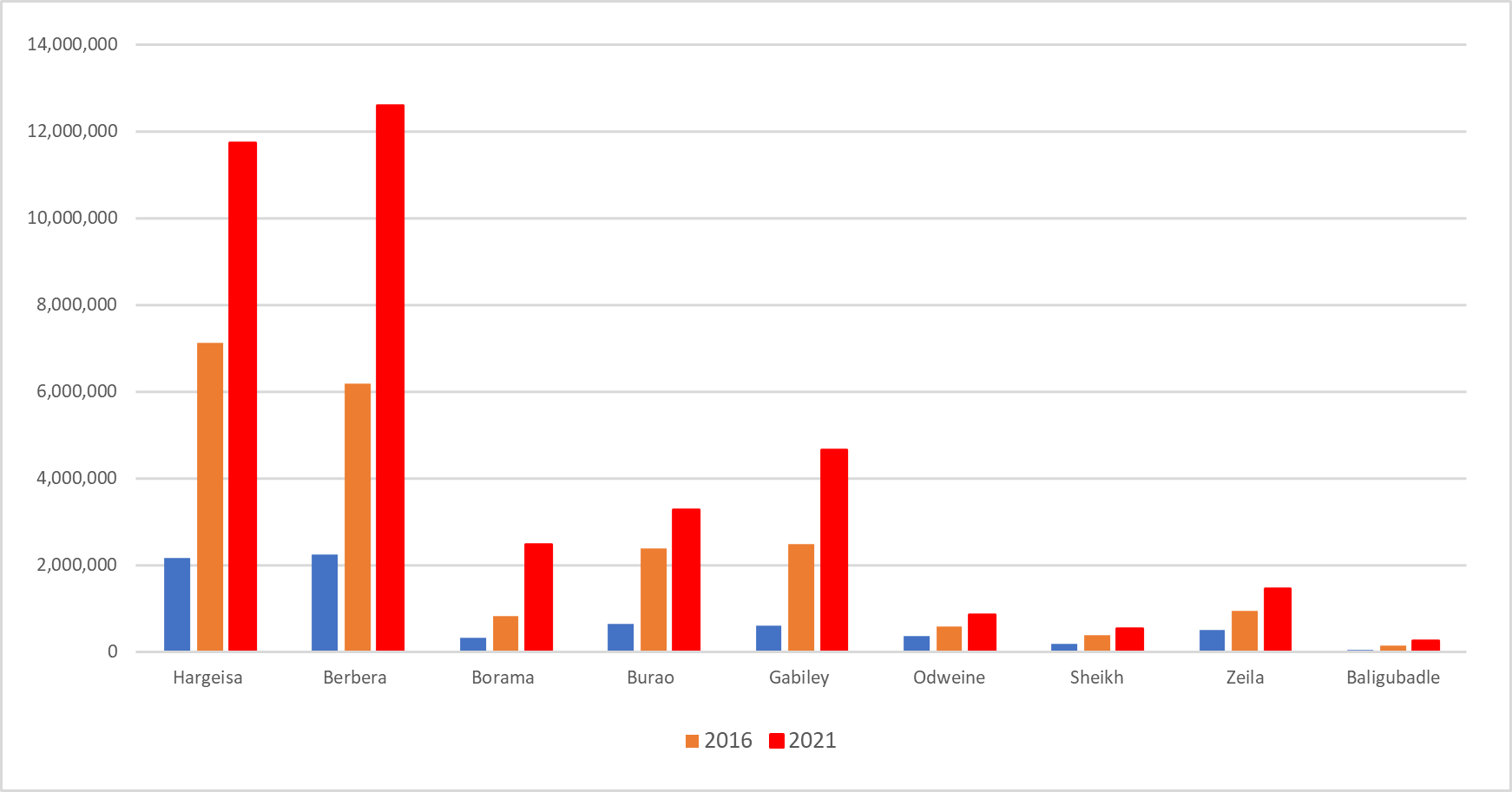

Figure 3: Somaliland revenue yields

One success story of the UNCDF/JPLG’s LDF model and broader fiscal

decentralisation thrust is how the transfer mechanism has been institutionalised in Somaliland. In March 2020, central and local governments in Somaliland began discussions on improving the intergovernmental fiscal transfers, culminating in revisions to Law No. 23 on Regions and District Self-Government, especially Articles 88 and 89, that captured the government’s commitment to fiscal decentralisation. Later that year, the Ministry of the Interior developed the District Grants Regulation No. 01/2020, with the support of UNCDF/JPLG and in cooperation with the Ministry of Finance, Office of the Accountant General, Auditor General and line ministries.

This regulation legalised and regularised the transfer of allocated funds from the government budget to local governments. These funds are allocated using a formula with set criteria and represent 12.5% of government revenue. From the beginning of 2021, with the support of the Ministry of Development Finance, the Accountant General’s Office and the Bank of Somaliland, the Ministry of the Interior made intergovernmental transfers to all 101 districts of Somaliland, including constituencies not funded by the JPLG. For example, the Somaliland government has adopted LDF mechanism to transfer resources to Sanaag and Sool, Regions not covered by JPLG. On the whole, it is important to underscore the point that, for the first time, Somaliland has a regular, transparent and objective transfer mechanism. These transfers significantly boost local governance and locally-led service delivery.

Three districts no longer require LDF support

In 2022, three municipalities (Berbera in Somaliland and Bosaso and Garowe in Puntland State) reached a critical milestone – ‘graduation’ – when JPLG support ceased to be an incentive. The three municipalities have fulfilled all the criteria for phasing out the LDF support, which represents just 1% of their total budgets, compared to 85% in 2011. The three districts have immensely improved many financial management performance indicators, consistently achieved unqualified audit outcomes, increased own revenues and put in place robust systems and public procurement procedures. Today, local services in the three districts are funded mainly through state transfers and own-source revenues. By phasing out support to these districts, where the LDF is having limited to no impact, JPLG can redirect funds to make a difference in other districts. It is important to note that these districts now have the capacity, systems, processes and confidence to access larger pools of funds, such as the World Bank and Somaliland development funding. Yet ‘graduation’ should not be perceived as achieving total independence because, going forward, these cities, their citizens and governments will continue to need technical and development funding, both from JPLG and other actors.

Own-revenues mobilised

The LDF support included assisting municipalities to assess revenue sources and implement revenue action plans. The result has been a phenomenal growth in own-source revenue in Somalia’s municipalities. This growth has been significantly assisted by JPLG’s targeted support in business registration and property tax sytems. Figure 3 shows a phenomenal growth in own-revenue trends for local authorities in Somaliland.

Investments catalysed

The LDF has been a catalyst for investments by the private and public sectors and communities. For example, road construction activated investments in shops, residential properties and health and education facilities. In the Burtinle district (Puntland State), the US$59,630 LDF grant for constructing a 300-meter long tarmac road stimulated districts and communities to mobilise additional funding of US$250,000 that was used to extend the road (to four kilometres) and to erect streetlights.

Conclusion

The LDF has not only transformed Somalia’s financial ecosystem but has improved lives and local governance. It has also created a relatively simple, objective, fair, reliable, and predictable intergovernmental fiscal transfer system that can easily be upscaled.