Why financial health must be treated as the true north to augment the success of financial inclusion

Authors:

Ankita Singh, Research and Insights Specialist

Mayank Jain, Data and Measurement Specialist

Jaspreet Singh, Global Lead - Financial Health and Innovation

Contact for more information:

Tags

Financial inclusion has taken remarkable leaps over the last decade, as reflected in the 2021 Global Findex survey. This is a cause for celebration as more people across the world can access formal financial services to achieve their personal and business aspirations.

However, true success of financial inclusion should not be judged on access and usage alone and equal emphasis must be placed on the financial outcomes that individuals and households seek.

Highlights of accomplishments in financial inclusion

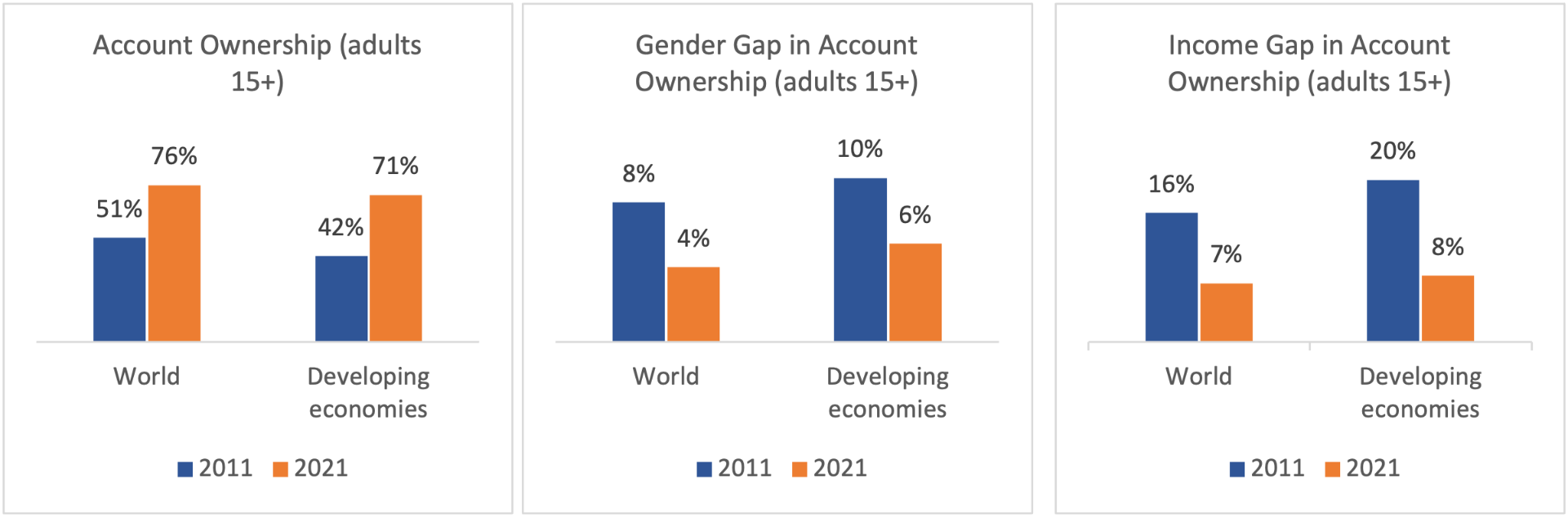

Over 3 out 4 adults (15+ years) across the world have an account at a bank or a regulated institution in 2021, a significant increase since 2011 when only 51% of the population had an account. Account ownership grew more rapidly in developing countries from 42% in 2011 to 71% in 2021. Furthermore, the share of inactive accounts has reduced since 2017 with only 13 percent of account owners reporting an inactive account in the past year in developing countries.

The large growth in account uptake also reduced the gender and income gaps globally and in developing economies. On average in developing economies, the gender gap in account ownership has reduced from 10% in 2011 to 6% in 2021, and the income gap has come down to 8 percentage points during the same period; indicating progress in bridging the gap in access to financial services for typically underserved adults.

Mobile money accounts have contributed extensively in growing account ownership and narrowing gender and income gaps, especially in developing countries and in Sub-Saharan Africa. Accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, in developing economies almost 6 out of 10 adults were making or receiving a digital payment, an increase of over 13% since 2017. This also indicates opportunity in improvement of access to domestic remittances, receiving government transfers and public pension, especially for the low-income populations.

Formal savings increased over the past decade across the world: Globally, almost half of the adult saved money in any form, while 42% adults saved in developing economies. More than half of the adults who saved in both high-income and developing economies did so formally. Moreover, mobile money is becoming an active instrument for saving in developing economies: nearly 39% of mobile money account owners saved using their mobile money account in sub-Saharan Africa.

An increase in formal borrowing is also observed in both high-income and developing economies. Nearly 50% of adults in developing economies borrowed money, but fewer than half used formal means such as taking out a loan from a regulated institution or using a credit card.

Examining consumers’ financial outcomes beyond access and usage

As we revel in the accomplishments in financial inclusion across the globe, we must also pause and examine the outcomes that people seek in their financial lives – the ability to manage day-to-day finances, be resilient in face of shocks, feel confident and in control of their financial situation, and be able to pursue opportunities. It is these outcomes that ultimately showcase the success or limitations of financial inclusion in improving people’s financial lives, especially in developing economies and among underserved populations such women and low-income.

Using the Global Findex data, we examine these four elements of financial health outcomes vis-à-vis financial inclusion progress, and identify the gaps that policymakers, financial service providers and development agencies must focus on to move consumers’ towards financial health.

Using the Global Findex data, we examine these four elements of financial health outcomes vis-à-vis financial inclusion progress, and identify the gaps that policymakers, financial service providers and development agencies must focus on to move consumers’ towards financial health.

Financial security and control indicate a worrying trend despite increase in account ownership

Constant worrying about falling behind on day-to-day or future finances reflect people’s subjective judgement of their low financial security and control. This feeling of financial vulnerability can occur among individuals regardless of their income status and can worsen during crises. Latest Findex confirms that in the developing world more than 6 out of 10 adults among the richest 60% income group feel somewhat or very worried about the potential for continued financial hardship because of COVID-19. Financial security of women and low-income was impacted disproportionately by the pandemic.

Poor financial health can have negative consequences on people’s mental and physical health, work productivity, social relationships, and the wider economy, as also reverberated in the UK’s financial wellbeing strategy.

Managing monthly expenses is a cause of worry: Globally, 65% of people were worried about not having enough money for monthly expenses or bills. This worry is more prevalent among the poorest 40% who have lower income and fewer income sources. What is equally concerning is that more than half of the richest 60% were worried about not having enough money to meet monthly expenses.

Women on average are more worried than men about paying for routine monthly expenses. In developing economies, nearly 73% of women say they are worried about not having enough money for routine monthly expenses as compared to 69% of men. Often in developing countries, women are responsible for taking care of household expenses such as food provisioning, utility bills, and paying school fees. However, in most cases, women are not the primary financial decision makers in the household resulting in a feeling of lower security and control over their finances.

Meeting medical expenses is the biggest financial worry in developing economies: Eighty percent of the adults in developing economies were worried about not having enough money to meet future medical expenses in case of a serious illness or accident. Even amongst the richest 60% of the population in developing countries, almost 75% are somewhat worried or very worried about their medical costs. Women on average are more worried about medical expenses than men in developing economies. Insufficient savings and low access to adequate health insurance and pensions respectively, are likely causes for these concerns among women and the poor.

Financing education is a cause of financial stress among low-income populations: Children’s education is a robust tool for low-income populations to climb out of the cycle of poverty. Investment in children’s schooling is therefore a significant financial priority in low-income households. However, globally and in developing economies, almost 6 out of 10 adults are worried about not being able to pay education fee for their children. This apprehension is higher for specific regions and segments. For instance, in South Asia, 85% of the poorest segment and 78% of women were concerned over their ability to cover educational costs. The financial stress around education in this region could emanate due to a high burden of education expense being borne by households themselves, with the poorest struggling to meet school expenses.

More people can come up with emergency funds but low reliance on savings indicates low financial resilience

Access to financial services should provide people with sufficient provisioning and cushioning to bear unexpected expenses and income shocks during crises such as ill-health or loss of income. When people build sufficient savings as well as access to affordable credit and insurance, they are better able to manage financial risks and remain resilient to shocks.

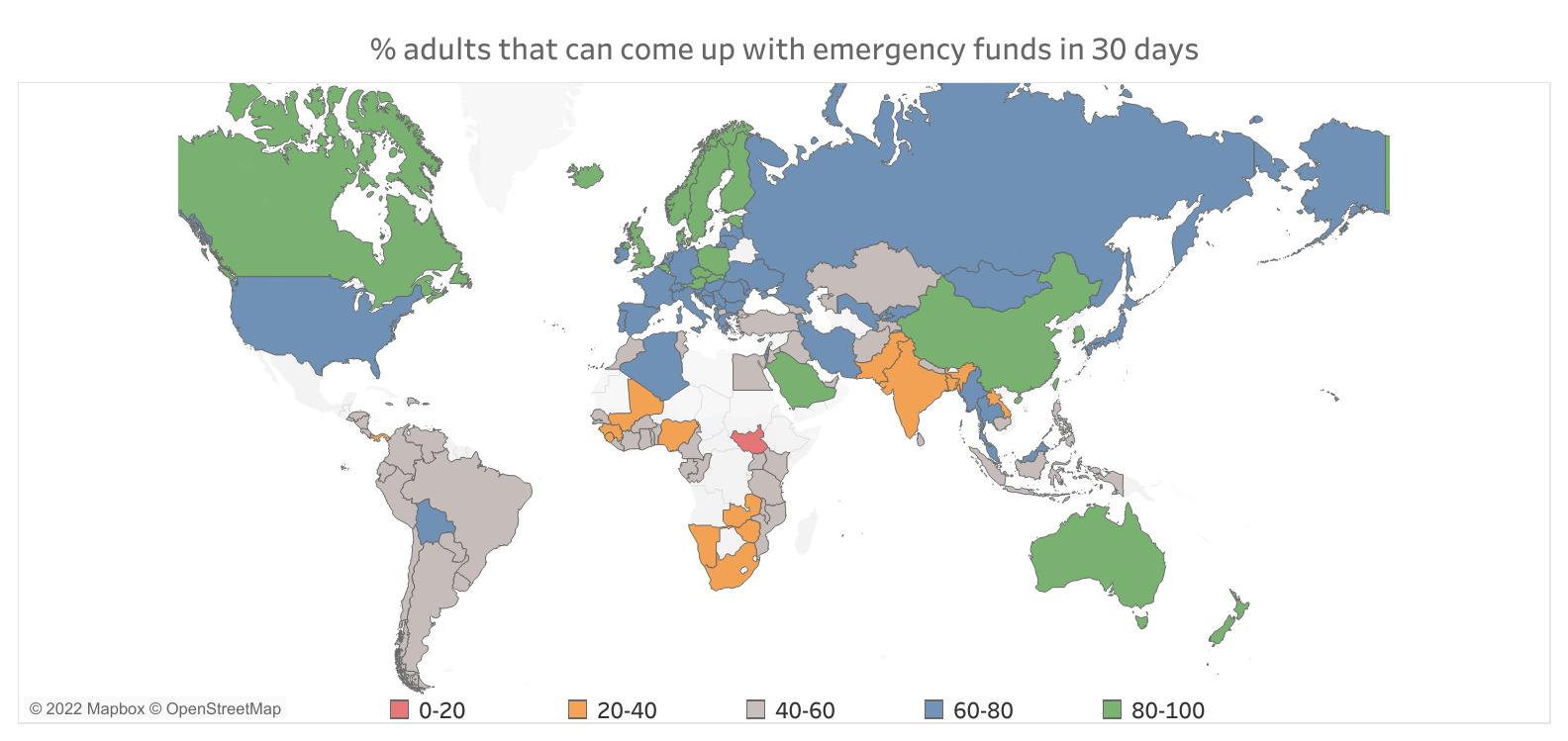

As per the 2021 Findex, only 55% of adults in developing economies could come up with emergency funds in 30 days without much difficulty, and only 41% adults can do so in 7 days. In low-income countries only 42% of adults could come up with emergency funds in 30 days without much difficulty, and a mere 26% of adults can do so in 7 days.

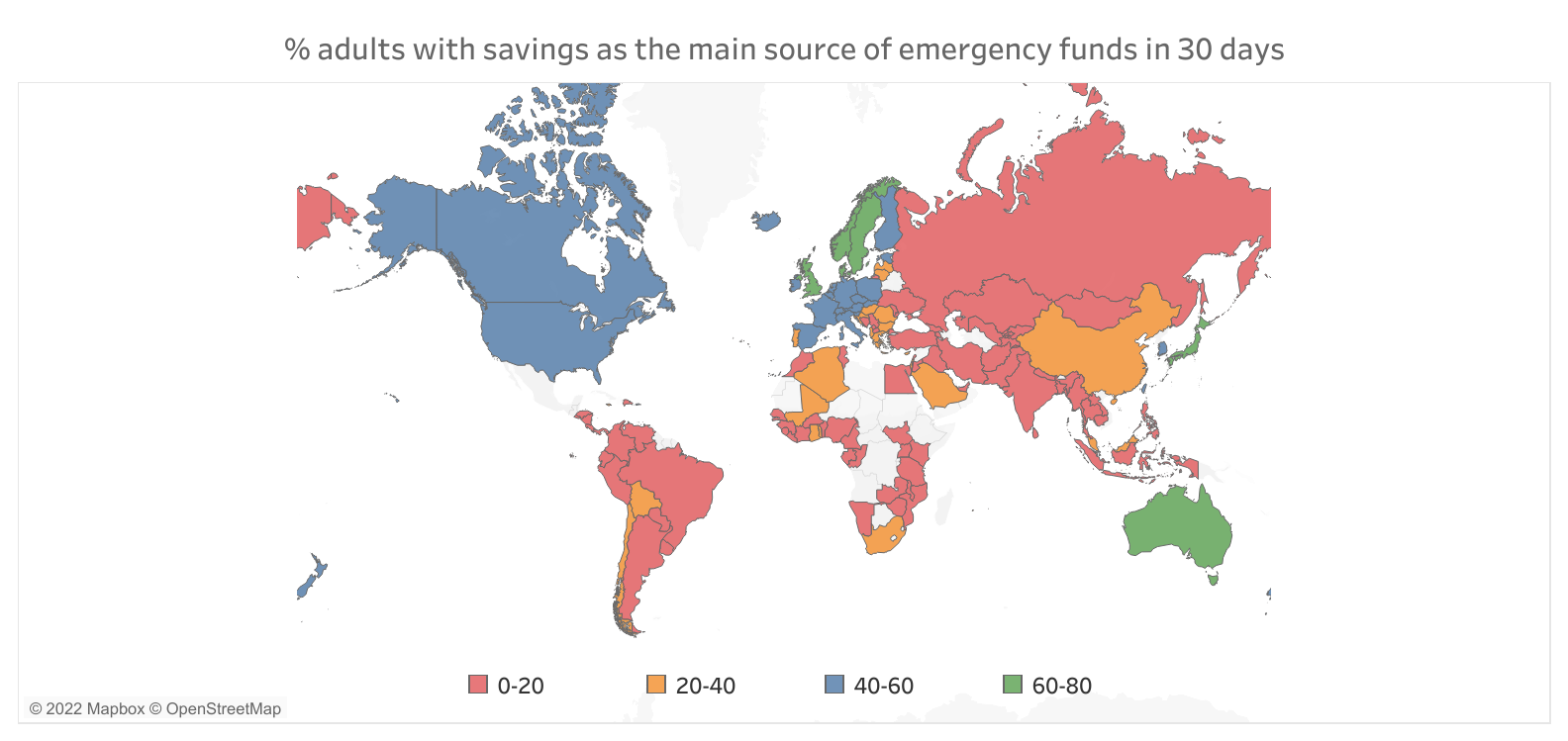

Financial resilience looks much worrisome if numbers are analysed vis-à-vis source of emergency funds. Only 1 out of 5 adults in developing countries relied on savings as their main source of emergency funds. This means that 4 out of 5 adults in developing economies do not have sufficient savings to cover unexpected expenses. Financial resilience does not seem strong enough in high-income countries either: only 5 out of 10 adults can come up with emergency funds.

Individuals and households also leverage other sources for emergency funds such as family or friends, borrowing from employer or bank, and selling household assets. In fact, family and friends continue to be the most common source of emergency money in developing economies especially for adults living in the poorest 40 percent of households and women. However, these funding sources do not guarantee timely financial support and can often be unreliable.

The gender gap in access to emergency funds is observed to be 8 percent, globally. This gap in financial resilience varies across regions and is much higher in lower-middle income and low-income regions. For instance, in South Asia women are 15% less likely to come up with emergency funds compared to men mostly because women rely heavily on family and friends for emergency money.

Research by the Financial Health Network shows that borrowing from family members and friends may reduce financial hardship, but it does not alleviate financial stress. The study observes that those who borrowed from family members to deal with the effects of a shock were likely to have slightly lower financial health scores than those who didn’t borrow. Further, the findings reveal that people who accessed funds from family and friends but were also saving for emergencies were associated with a 25% lower risk if hardship. Having access to emergency savings and financial support from family can act as a double layered firewall during financial shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic.

4 out of 5 adults in developing economies do not have sufficient savings to cover unexpected expenses.

It is noteworthy that the share of adults who save in any form in developing economies has not changed since 2017. While the Covid-19 pandemic is likely to have influenced this stagnancy or even depletion in saving as the crisis led to massive job losses and labour market disruption, evidence of poor resilience was present in pre-pandemic years as well. Various pre-pandemic studies show that majority of the population in many emerging and advanced countries were financially ill-prepared to weather a prolonged income shock. For instance, according to a study by FSD Kenya that mapped global financial resilience in 2017, more than two-thirds of adults in Kenya, Vietnam, Greece, Chile, Colombia and Bangladesh would not be able to cover basic needs for three months using just their savings or by selling assets in the event they lost their incomes. Another study suggested that more than 50 percent of households in emerging and advanced economies were not able to sustain basic consumption for more than three months in the event of income losses. Many households and firms in emerging economies were already burdened with unsustainable debt levels prior to the crisis and struggled to service this debt once the pandemic and associated public health measures led to a sharp decline in income and business revenue.

In the post-pandemic world, resilience of low-income populations continues to be tested. Over 3 out of 5 adults in the poorest 40% were very worried that that they will experience or continue to experience severe financial hardship because of the disruption caused by COVID-19. More than half of women felt the same way. In this context, it becomes critical to understand and address the savings behaviour to build a stronger safety net for households and communities to be more financial resilient in the face of future challenges. Behavioural interventions that encourage regular savings combined with appropriate supply-side measures that make (goal-based) savings easier and an attractive option for vulnerable and excluded populations are the need of the hour for building a more resilient future.

More people are saving formally but few are saving for old age

Research has long shown that retirees suffer from a variety of economic hardships, even in developed economies that enjoy relatively strong pension systems. While longevity brings with it a wide variety of opportunities for the society, it also poses new challenges for policymakers and service providers seeking to achieve financial health of the society. In developing countries, inadequate pensions, and savings among large proportions of adult populations and weakening community-support system are a serious cause of concern. Traditional employment-based pension systems and retirement saving mechanisms are not available to the informal sector. As a result, a large segment of society is excluded from being financially secure, posing potential financial challenges in their old age.

Today, many adults lack financial planning to build sufficient savings for old age. Globally, 1 out of 4 adults saved for old age, whereas in developing countries only 19% of adults did so even though pension coverage in the latter is very low. What is even more worrying is that only 24% of richest 60 percent adults in developing countries saved for old age, suggesting a clear need to boost financial literacy and financial planning.

Findex survey also finds that almost 3 out of 4 adults in developing economies are worried about not having enough money for old age. It may appear that this issue is more prevalent among the poorest 40% of the population. However, even among the richest 60% of the population in developing countries, nearly 70% of adults are worried about their future expenses in old age. As a result, while high-income populations may appear to be financially healthy, in reality they may not have control over their future financial goals.

Even among the richest 60% of the population in developing countries, nearly 70% of adults are worried about their future expenses in old age.

Considering that the share of older adults in the global population is projected to double by 2050, policymakers and financial service providers must pay a closer attention to retirement savings and pensions. Focus on financial planning at an earlier age and improving participation in savings plans can offer solutions. Studies suggest that digital financial services can help people to prepare better for the financial challenges of old age. For instance, regularly scheduled transfers from mobile money accounts into interest-bearing savings accounts at financial institutions might offer long-term savings possibilities in economies with high mobile money penetration. However, even though DFS play a pivotal role in preparing for old age, broader safety nets remain critical for the well-being of older adults.

Shifting focus towards financial health is an opportunity and absolute necessity to build resilient and prosperous societies.

Financial inclusion is undeniably a key enabler to economic growth and development. But to reap the full benefits of financial inclusion, policy and financial service providers need to look beyond number of accounts and financial transactions and shift their focus towards building people’s financial health.

It is through positive financial outcomes that countries can realise several sustainable development goals including no poverty, good health and well-being, quality education, energy access and economic growth. Putting financial health at the heart of national financial literacy and inclusion strategies, and banking is a a good place to start.

Unlocking different financial health-centric strategies and tools is fundamental to build resilient societies and achieve the SDGs. Towards this, several supply and demand side measures can be employed by public and private stakeholders. However, certain foundational elements such as designing affordable savings systems and products and encouraging financial planning at an early age, are areas that need focused attention. In our follow-up analysis to this piece, we explore these tools in context of specific countries and population segments to identify action points for the involved public and private stakeholders.

Reference reading: Readers can also refer to our brief for Banks on steps to align business strategy with customers financial health and for Insurance providers on examining consumers financial health data for moving the insurance focus from risk protection to risk prevention and wellbeing.